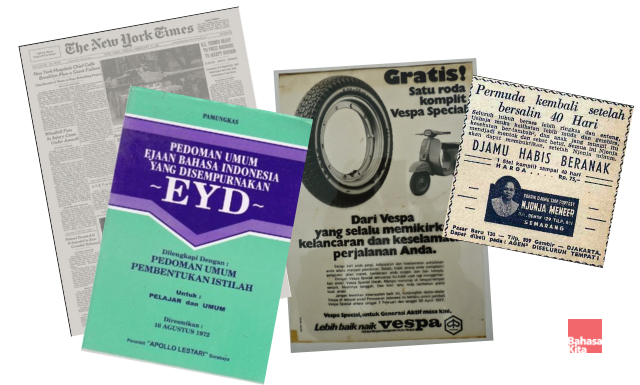

This week we came across a digitized version of an article from The Times’s print archive about Indonesia 1972 Spelling Reform. It was originally published on August 13, 1972 before the start of online publication in 1996. We found the article is very informative for those who is interested in the history of Indonesian language. Specially because the article is preserved as they originally appeared. We decided to share the article on Bahasa Kita for you. Enjoy 🙂

Indonesia Plans Reforms in Spelling

JAKARTA, Indonesia, Aug. 9 —The Indonesian Government has decided to take the “D” out of “Djakarta” and make other spelling changes designed to take some of the mystery out of the pronunciation of its national language, a form of Malay.

Similar changes are also be ing made in Malaysia to make the languages of the two coun tries, which are spoken virtual ly the same way, conform In written form. But spelling changes in Malaysia, which was under the influence of British colonials, will be less radical than those in Indonesia, which evolved under Dutch colonial ism. The two countries hope to see their compromise form be come a powerful regional lan guage. Malay is already widely spoken in Singapore, southern Thailand and the Philippines.

Malaysia and Indonesia have been discussing ways to make their languages conform in written form since the middle nineteen‐fifties. A study in 1957 proposed that a new common language called Malindo be adopted. It would have been basically the same spoken language with spelling compromises that would have allowed Indonesia to move toward Ma lay spellings without Indonesia’s leader at the time, President Sukarno, being accused by the 110 million Indonesians of capitulating to the spelling system of 12 million Malays.

Malay Was Chosen

Language was used by President Suharto as a vital tool in creating a national spirit out of Indonesia’s many island cultures and their diverse ethnic and regional language differences. Rather than adopt Javanese, the tongue of Indonesia’s postwar ruling classes, he chose Malay, which was not the entrenched language of any one island culture.

The effect of the changes, to go into effect over five years beginning this month, will be the “Englishization” of Indonesian spellings. But a few of the changes are strange enough to leave the unfamiliar linguist with the feeling of having mouthful of marbles.

Many English writers and publications have long taken license with Indonesian spelling to the disdain of purists who contend that simplification subtly changes the sounds of words. A few Indonesians even contended that this alteration was an anti‐Indonesian slap.

For example, Jakarta, the capital, is spelled “Djakarta” in Indonesia, and to sensitive ears, there is a slight difference in pronunciation. The sound of the “Djakarta” spelling is cross between the “j” sound and the “ch” sound. Under the new rules, it becomes officially spelled Jakarta.

Currently the word for street in Indonesia is spelled “djalan” and in Malaysia, “jalan.” Under the new form, all words begin ning with “dj” will begin with “j” dropping the “d”.

In regular Indonesian, a “j” by itself is pronounced like a “y” Under the new rules “y” sounding “j’s” will become “y.” Under the new rules “y” themselves. The name of the Minister of Trades is Dr. Sumitro Djojohadikusumo. Theoretically, it would now be spelled Djojohadikusumo. — which is more like it sounds: Joey‐o‐hod‐ee‐co‐soom‐oh. But changes of spellings of people’s names are not mandatory.

Similarly, “sj” will become “sy” and “nj” will become “ny.” But somewhat controversially, “tj” —which sounds like “ch”—will become, simply “c.”

This last change is probably best explained by using an Eng lish word, say, chat. Under the old Indonesian spelling system, it would be spelled “tjat.” Now it would be spelled “cat,” and pronounced “chat.”

Five new letters, “f,” “v,” “z,” “q” and “x” will be added to the alphabet under the new spelling system to expand its scope—but where these letters will be used is open to question.

The old Dutch bugaboo “oe” will become “u.” The Government tried this change two decades ago with only partial suc cess. Former President Sukarno signed his name “Soekarno” regardless of how English writers spelled it. President Suharto’s name is also widely spelled “Soeharto,” and more often pronounced “Sowharto” than “Sueharto.”

A version of this archives appears in print on August 13, 1972, on Page 18 of the New York edition with the headline: Indonesia Plans Reforms in Spelling.