Last updated on January 25, 2024

If someone tells you that Indonesian spelling and pronunciation is relatively easy, it’s true! But I’ve also heard some exaggerated claims like, “Every word is pronounced exactly how it’s spelled,” or “Each letter is always pronounced the same way.” That’s normally true, but it’s not always the case.

Orthography

In linguistics, the system used to represent a spoken language in writing is called an orthography. There are all kinds of orthographies, but both English and Indonesian use an alphabet. Alphabets are often presented as if each letter represents one sound, but the reality is a bit more complex. English orthography is notorious for its complex rules full of exceptions. (Does any other language have a spelling bee?!) Indonesian orthography is much more orderly, but not without a few twists of its own.

Indonesian Orthography

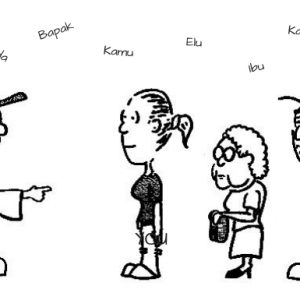

One of the first Indonesian words anyone learns is Pak which means “sir” or “Mister”. Without even noticing, most learners will quickly pick up on the fact that the letter k at the end of this word is not always pronounced—or at least it is not pronounced the same way as k in most other words in Indonesian. The word Pak is normally pronounced [paʔ] (in IPA), with a glottal stop at the end of the word. So k is normally pronounced as you might guess, [k], but at the end of some words, like Pak and tidak, the k is not pronounced the same way.

Another letter with an exceptional pronunciation in a few words is h. The word tahu can mean either “tofu”, if the h is pronounced, [tahu], or “to know” if the h is not pronounced. [tau]. (Actually, in casual contexts, Indonesians won’t even bother writing the h.) The letter h is also often not pronounced at the end of words. The letter z is another with multiple pronunciations, sometimes changing from person to person. For example, the word zaman ‘age’ or ‘time period’ is pronounced by some people like the z in English, and by others like the j in English.

The Vowel e

A much more pervasive case of a letter with more than one pronunciation is the vowel e. This letter is sometimes pronounced like the schwa sound, [ə], and sometimes like the vowel in the English word bed, [ɛ]. The spelling doesn’t tell you which way to pronounce the word, but if you’re a native speaker you already know how it should sound, so it’s no problem. For foreigners wondering how to pronounce a word, you can check the SEAlang online Indonesian dictionary that marks all the [ɛ] words with an acute accent, é.

Digraphs

When two letters are combined to represent a single sound, this is called a digraph. English has digraphs like sh for the sound written in IPA as [ʃ] and th for the sounds [θ] and [ð]. When we learned the Indonesian alphabet in class we were taught two digraphs: ng for the velar nasal [ŋ] and ny for the palatal nasal [ɲ]. (We don’t have that sound in English but it’s the Spanish letter ñ.)

There are two other digraphs in Indonesian orthography that are not normally included in the alphabet. One is sy for [ʃ], sometimes pronounced [s]. The other is kh which can also be pronounced in different ways, such as [x] in akhir “end” or as [k] in khusus “special”. These digraphs are only found in words that come from Arabic.

Pointing out these exceptional patterns is not a criticism of the Indonesian orthography. The orthography is just fine with all of these exceptions—and that’s the interesting part! Where did these exceptions come from? And how do Indonesians learn them? Those are the kinds of questions a linguist might ask.

Further resources on Orthography:

Beginner:

An introduction to the writing system of the world by Omniglot.com.

Intermediate:

A video on the history of English orthography.

Advanced:

A paper by Elke Karen and Michael Cahill on Factors in designing effective orthographies for unwritten languages.

About the author: As a linguist, Joseph Lovestrand is mostly interested in studying indigenous languages, and seeing what they have to tell us about how we communicate, think and live. His research began in Africa. He lived for a year in Chad, studying the Barayin language in order to help them establish their first ever literacy program. He also spent four years working in Cameroon where he managed projects supporting indigenous language communities and did field research on the Nyokon language. His most recent linguistic work has been in Indonesia, where he has consulted on a literacy program for the Kodi language in Sumba. Read more at: www.josephlovestrand.com