Last updated on January 25, 2024

The technical term “point of articulation” or “place of articulation” comes from the field of articulatory phonetics. Phonetics is the study of the sounds of speech. Articulation refers to the mechanics of making sounds for speech. There are usually several things happening at once when we make a sound for speech, but the relevant part here is where you put your lips and tongue.

Prefix me-

When I was learning about verbs in formal Indonesian, I was told about a prefix me- that is used with transitive verbs—verbs that can have a subject and an object, for example membeli ‘buy’ or mencari ‘look for’. This prefix is pronounced in different ways depending on what verb it attaches to. As a student, I was given a list of examples something like this:

- mem– when the verb root starts with p or b

- men– when the verb root starts with c, j, t or d

- meng- when the verb root starts with k, g or any vowel

- meny– when the verb root starts with s

- me- when the verb root starts with l or r

Five ways to write one prefix! This may seem like an arbitrary list to memorize, but any linguist will immediately spot a pattern that explains at least some of the changes. The pattern relates to a process with a long technical name: assimilation to the place of articulation.

Assimilation to The Place of Articulation

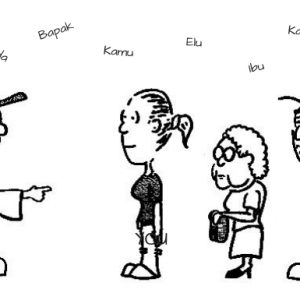

Assimilation just means “to become the same”, and the rule basically comes down to this: when you make the last sound of the prefix, put your lips and tongue in whatever position they will need to be in for the next sound—the first consonant of the verb root.

If you make a p sound (like the English word “pat”) you will notice that your lips have to touch to make this sound. The same thing happens when you make a b sound (as in “bat”) or an m sound (“mat”). These three sounds have the same place of articulation. They use two lips, so we call them bilabial sounds. For this reason, it is no surprise that m goes with p and b, like the word membeli ‘buy’.

The Alveolar Ridge

The same thing is true of n, t, and d. If you say the English words “new”, “too” and “do”, you’ll notice that for the first sound in each of those words your tongue touches the same place in the front of your mouth. That place is called the alveolar ridge. These three are alveolar sounds.

The Velar Sounds

The sounds ng, k and g are called velar sounds. For example, the last consonant in the English words “bang”, “back” and “bag” all end with the tongue in the same place: in the back of the mouth near the velum. Note that even though both Indonesian and English write the ng sound with two letters, it is just one sound. The symbol used in the International Phonetic Alphabet for ng is [ŋ].

The Nasal Sounds

Nasal sounds like m, n and ng are particularly likely to copy the place of articulation of an adjacent sound, just like we see with this prefix in Indonesian. Actually, a very similar pattern can be found in English. A small number of adjectives can take a prefix that negates the meaning, but the suffixes changes depending on what word it attaches to. So possible becomes im-possible, but tolerant becomes in-tolerant. Never in-possible or im-tolerant.

Some of the other patterns of this Indonesian prefix me- are a bit more complex, but there are phonological reasons why Indonesian speakers pronounce this prefix in so many different ways. Well, actually the meny- suffix before verb roots starting with s is a bit strange! Languages tend to follow general patterns, but they are also full of apparent exceptions that can surprise us and make us think more deeply about why languages are the way they are.

Further resources on Phonology:

Beginner:

A video from The Ling Space on the International Phonetic Alphabet.

Intermediate:

A blog by Superlinguo with lots of links to learning about the IPA.

The Virtual Linguistics Campus video on assimilation.

Advanced:

A set of lectures on Phonology from The Virtual Linguistics Campus.

About the author: As a linguist, Joseph Lovestrand is mostly interested in studying indigenous languages, and seeing what they have to tell us about how we communicate, think and live. His research began in Africa. He lived for a year in Chad, studying the Barayin language in order to help them establish their first ever literacy program. He also spent four years working in Cameroon where he managed projects supporting indigenous language communities and did field research on the Nyokon language. His most recent linguistic work has been in Indonesia, where he has consulted on a literacy program for the Kodi language in Sumba. Read more at: www.josephlovestrand.com